Overview

What is the Niagara Escarpment? Where can it be found? How vital is it to the economic, social and environmental resources of Northeast Wisconsin?

Our aim is to share the beauty and importance of the Escarpment community-wide, helping to acquaint local residents with the particular needs and issues related to the Escarpment landscape. That’s why we intend to create educational brochures, maps, curricula and other informational materials to help both students and adults understand the Escarpment’s connections to the economy, ecology and identity of the region.

Escarpment fun facts:

The first outcropping of the Niagara Escarpment can be seen in Southern Waukesha County at “Brady’s Rocks” along the Ice Age Trail in Southern Kettle Moraine State Park.

The Escarpment extends 230 miles in Wisconsin.

The Escarpment corridor hosts more than 241 rare species including the Dwarf Lake Iris, Hines Emerald dragonfly, and cedar trees more than 1,000 years old.

It houses archeological assets in the form of Native American petroglyphs, pictographs and effigy mounds.

The ‘Wisconsin Ledge’ American Viticultural Area (AVA) owes its ability to grow grapes to the Escarpment’s special geology, soils and climate.

Niagara escarpment 101

Below is a basic tutorial for understanding what the Niagara Escarpment is, how it was formed, how it influences the environment and community, and how humans have impacted this important corridor over time. Click on any one of the headings below to expand that section. A listing of additional resources is provided within each section.

Definition & Formation Process

The Niagara Escarpment is a prominent rock ridge that spans nearly 1,000 miles in an arc across the Great Lakes region, forming the ancient “backbone” of North America. It runs from eastern Wisconsin to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, through southern Ontario to western New York State, where Niagara Falls cascades over it, giving the escarpment its name. The red line on this map shows the path of the Niagara Escarpment.

In Wisconsin, the Niagara Escarpment is a discontinuous ridge that stretches about 230 miles from Waukesha County north to Rock Island at the tip of Door County. It is highest along the western edge of Door County, where it reaches a height of about 250 feet above Green Bay.

So what exactly is an ‘escarpment’? An escarpment is the steep cliff edge of a cuesta, which is formed from slightly tilted layers of rocks. The steep cliff face forms when crumbly rocks, such as shale, are eroded from beneath erosion-resistant rocks like limestone or dolomite, which then break off to make the cliff face.

The rocks of the Niagara Cuesta were tilted when the Earth’s crust sagged, forming a bowl-shaped depression beneath Michigan. The Niagara Escarpment is the exposed, up-tilted, outer edge of this feature. The lands behind (to the east in Wisconsin’s case) are referred to as the Niagara Cuesta. A cuesta, or sometime referred to as a ‘dip-slope’, is the term used to describe the lands located behind an escarpment. The Niagara Cuesta is comprised of the same underlying highly fractured bedrock, some of which is close to the surface and contains karst features.

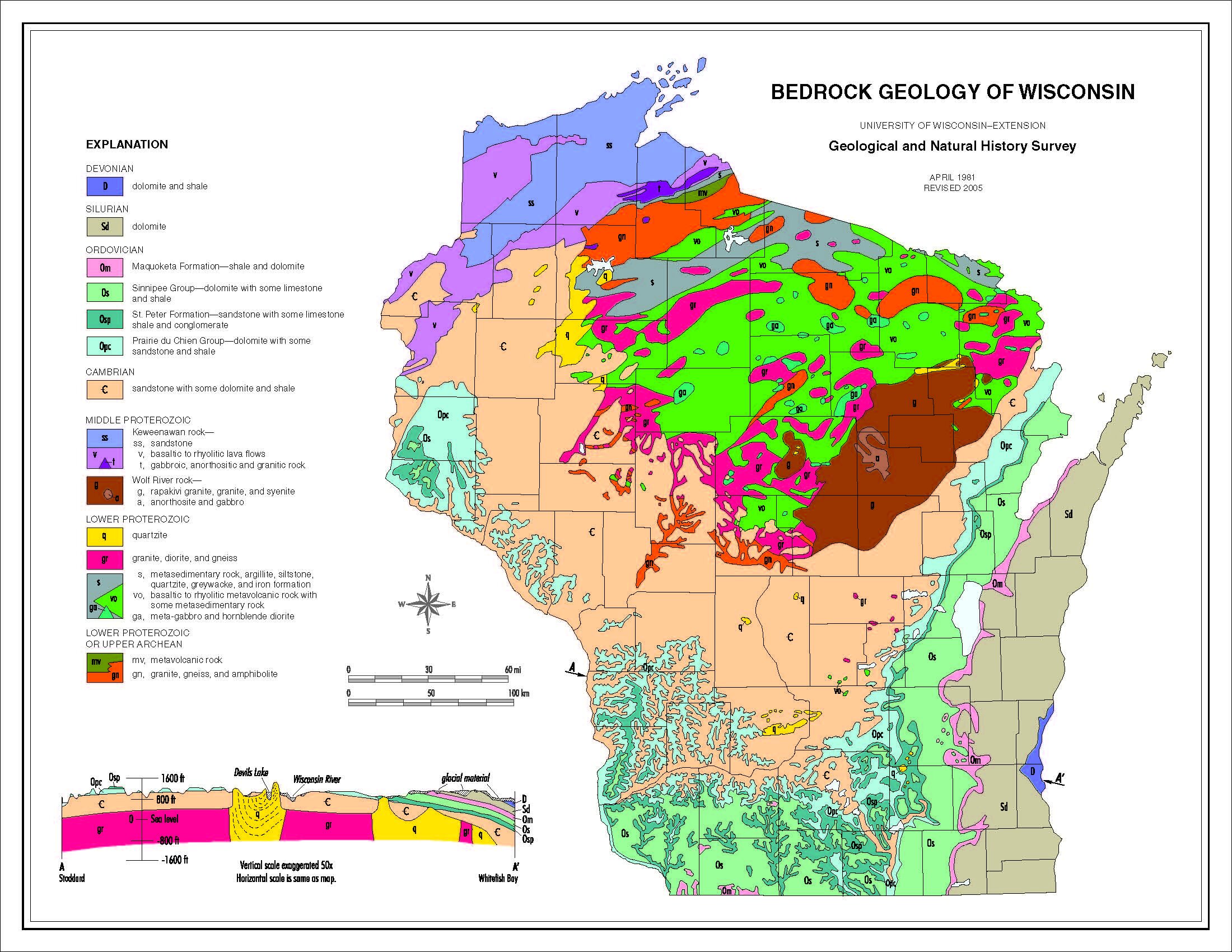

The rocks in the Niagara Escarpment were deposited during the Ordovician and Silurian periods of Earth’s history, about 450 to 430 million years ago. At that time, this part of North America was located about 20 degrees south of the equator. Shallow tropical seas, like those in the Bahamas today, covered the region. The rocks started as layers of mud on the ancient seafloor. Numerous nearby catastrophic upheavals, along with changing drainage patterns deposited layer after layer of mud and debris to form this sedimentary rock. Evidence of these shallow seas exists in the form of fossils and reef formations.

“Niagara Escarpment: A discontinuous bedrock-controlled, geomorphologic feature composed of any and all outcrops that form a rock ridge or series of ridges at the bedrock surface along the ‘western’ edge of the Silurian (‘Niagaran’) outcrop belt.”

To illustrate the massive changes occurring during the escarpment’s creation, consider that at one time, the Great Lakes system used to exit from a location on the east side of what is now the Georgian Bay, not the current St. Lawrence Seaway route. In fact, evidence of an ancient massive waterfall exists between the tip of the Bruce Peninsula and Flowerpot Island which plunged some 300 feet. Further connections have been made between ancient First Nation stories and current-day geologic/hydrologic research by the Canadian Government.

More recently….about 30,000-40,000 years ago.....during the beginning of the first ice age, the now hard dolostone comprising the western edge of the Michigan Basin was buried under thin layers of sediment and soil. In fact, the landscape at that time did not necessarily have an ‘escarpment’ that would have been prominent. As the vast glaciers moved south from Canada, they split into two lobes, mainly due to the existence of this “hard edge” starting in the northern reaches of Door County. These split lobes not only exposed many portions of the cliff-face by scouring soil and rock materials from and below its face, but they also created the Bay of Green Bay, Lake Winnebago, and Lake Michigan. As the ice melted, water surged into rock fractures along the escarpment creating its extensive karst and cave system.

Bedrock Geology, Karst & Caves

The previous section provided an overview of how the current-day bedrock was formed and shaped to create the linear cliff feature we know of as the Niagara Escarpment. Many more unique and interesting aspects of this bedrock exist that help to understand why the escarpment is such a unique and valued resource, including:

It is highly fractured

It dissolves easily

It is underlain by a nearly impervious layer of shale which prevents vertical groundwater movement

It is a highly valuable building material

The Niagara Escarpment and Cuesta are considered to be a ‘karst’ landscape, which means it has a highly fractured – and dissolvable – dolomite geology. This type of geology causes fractures, sinkholes and caves to appear, and creates an environment where groundwater is highly prone to contamination. The Niagara Escarpment is an important source of groundwater and drinking water for local residents. Private wells must be maintained, and tested regularly, and the impacts of new or existing land uses need to be carefully considered when living along the Escarpment corridor.

The Niagara Escarpment corridor is home to the most underground cave systems found anywhere within Wisconsin. Cave features were created as the glaciers left and significant amounts of melt-water traversed the highly soluble karst landscape. Sinkholes and other conduits at the surface allowed for glacial melt-waters to dissolve and wear away the underlying dolostone as surface water becomes groundwater that finds the path of least resistance. Dozens of caves are known to exist along the Niagara Escarpment corridor, including two of the three longest cave systems the State. Many of these caves are on private land and therefore are inaccessible to the average person. However, two publicly accessible cave systems exist at the Ledge View Nature Center just outside of Chilton (Calumet County) as well as caves located at the Cherney-Maribel Caves County Park, in Manitowoc County. The State’s caving club – the Wisconsin Speleological Society – often hosts tours of these caves and they can be contacted for more information.

Flora & Fauna

The Escarpment is home to many unique plants and animals, The Niagara Escarpment and its associated corridor harbor some of the highest levels of biodiversity within the State due to its unique bedrock structure and interactions with the groundwater system. Having both severe and highly moderated environments in close proximity. At least 241 rare and endangered species have been found living amongst its cliff faces and other unique habitats. While not considered endangered, other unique species and habitats such as ancient white cedar trees, bats, and remnant oak savannas also need protection.

Watersheds & Waterfalls

The Niagara Escarpment is a major determinant of surface water drainage, as its linear cliff face nearly mirrors that of the western edge of the Lake Michigan Basin. As implied by the definition of a cuesta (or dip-slope) most surface water drains easterly, away from the face of the escarpment.

The Niagara Escarpment is a major determinant of surface water drainage, as its linear cliff face nearly mirrors that of the western edge of the Lake Michigan Basin. As implied by the definition of a cuesta (or dip-slope) most surface water drains easterly, away from the face of the escarpment.

Cultural Landscape

For centuries, American Indian tribes, the original settlers of the landscape, considered the Escarpment a sacred place. Whether used for settlement, as a guide for travelling, or for religious purposes, it was a revered and important element of these cultures. Evidence is provided through archeological and historical research as well as the existence of ancient petroglyphs, petroforms, and Woodland Period burial mounds.

The Escarpment corridor also has significant historic sites, some dating back to Paleo-Indian times (10-12,000 years ago). More modern historic structures such as lime kilns, cemeteries, and churches exist and are important as well.

In the 1800’s, the escarpment was (and still is) an important source of stone for building, lime production and road construction. Numerous lime kilns are scattered across the corridor and provide a reminder of the escarpment’s role in the development of its early settlements and cities, including their economy.

Values

The Escarpment is used by our society in many ways, and is a much-beloved part of the landscape in Wisconsin, offering spectacular vistas, inviting scenery, and opportunities for reflection, recreation, and education. The escarpment corridor has also provided numerous resources that serve a valid purpose today, much as they have for hundreds, if not thousands of years. Uses such as agriculture, mining, and wind energy serve a value to society, however; it is easy to see that many times, the uses and/or values can conflict.

Furthermore, no comprehensive plan for the conservation and use of the corridor exists in a form that truly recognizes and balances its resources, as well as the values of our society. The Niagara Escarpment Resource Network hopes to foster the development of plans that achieve a greater acknowledgement of this feature’s global significance, while accommodating the needs of modern day society.

Ask yourself…………. What is the ‘value’ of the Niagara Escarpment’s:

Historic & Cultural Resources?

Viewsheds & Vistas?

Unique Habitats?

Endangered Resources?

Groundwater & Drinking Water Resources?

Mineral Extraction?

Housing & Economic Development?

Tourism and Geotourism?

Wind Energy Potential?

Agriculture?

Viticulture (grape growing)?

Recreation?

Leisure?

Stormwater Management (green infrastructure)?

Climate Change Resilience?